Centering Children, Evidence, and Quality in Screen Time Debates

Why quality and evidence should guide whether and how technology is used in children’s education

With growing anti-tech and anti-screen movements for young children across Europe, the Nordics, and much of the Global North, we are often asked a familiar question:

If you work in EdTech, do you think screens are always a good thing?

We hear this from parents, educators, and policymakers alike. Some argue that children would be better off abandoning screens altogether and returning to paper, pencils, and analogue play. Others - often in lower-income countries- are making extraordinary sacrifices to buy phones or tablets so their children can access learning content at all.

This contrast of Global North-Global South narratives about screen time matters (the international perspective in our name is not incidental!). Across the Global South, EdTech is often seen as a gateway to opportunity: access to learning materials, teachers, and resources that would otherwise be out of reach. In parts of the Global North, screens are increasingly framed as a threat to childhood, wellbeing, and learning. These positions are often driven by strong emotions and lived experiences, on all sides.

Our role is not to dismiss the children’s screen debate but to bring scientific evidence into the conversation.

In our projects, we ask different questions:

What is the added value of a screen in a given context? Can its use, design, and content be optimised to support learning and development? And if a screen is not adding value, what is the evidence-based case for reducing or removing it?

A key nuance often missing in screen-time debates is the assumption that EdTech is always about screens. In reality, educational technology has taken many forms over time. Radio, for example, remains an effective educational technology globally, particularly in contexts where internet connection is missing or unreliable. We therefore recommend focusing on the function of the technology rather than whether it is technology or not.

Crucially, we approach EdTech questions through an equity lens. Blanket “no screens” policies can unintentionally disadvantage those already on the margins, including children with special educational needs who may rely on digital EdTech to communicate, learn, or participate fully in a classroom.

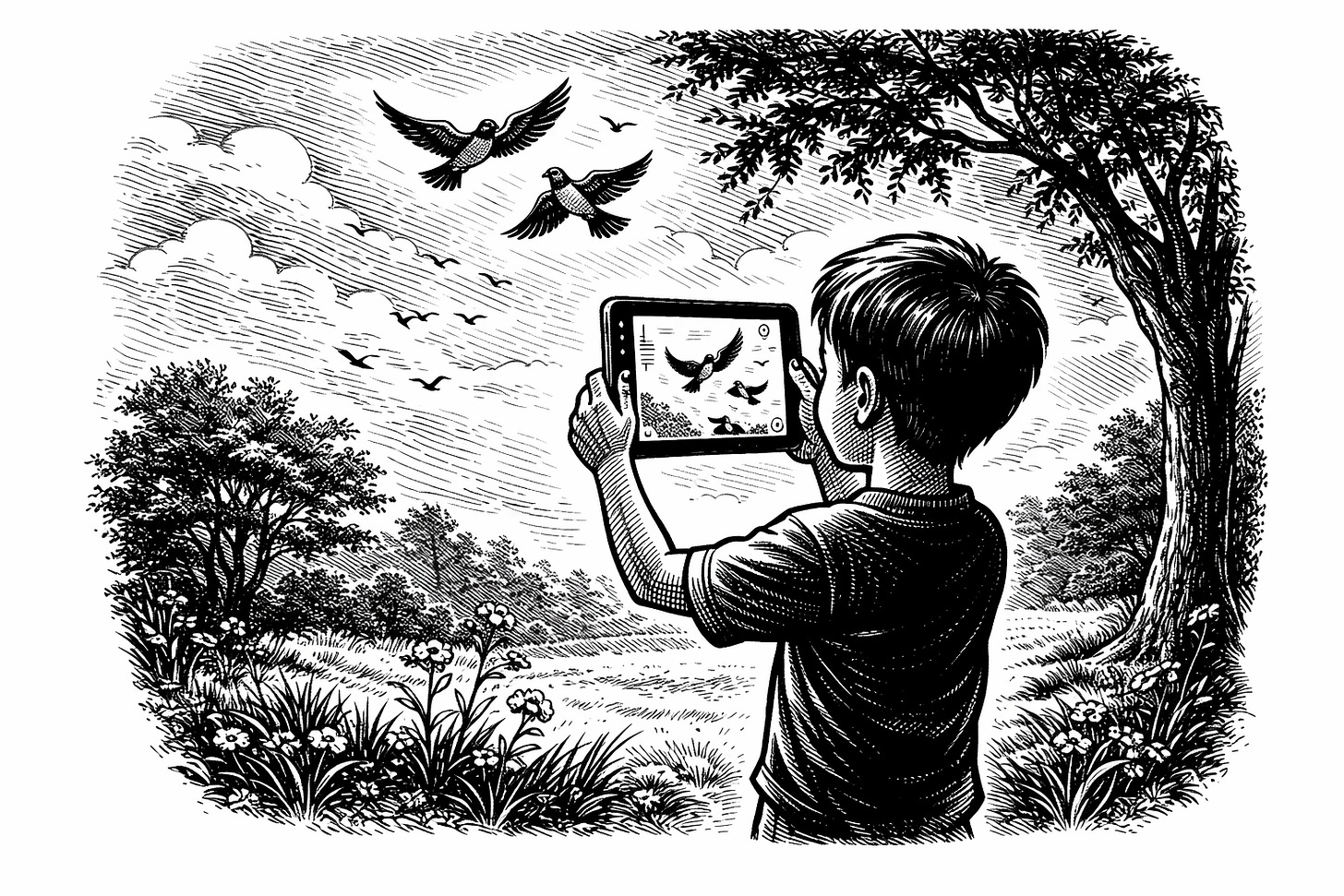

We also challenge a common but misleading dichotomy: that being outdoors means being screen-free, and being indoors means being on a screen. Screens can be used outdoors to explore nature, document observations, or create stories to share with family members and friends. Likewise, indoor play does not have to be digital. In research, learning and play are not neatly divided into “online” and “offline” worlds.

Image created with ChatGPT Pro 5.2

We are not naïve about the risks. We are acutely aware of the darker sides of the EdTech industry, including the significant lobbying power of large technology companies, the dangers of unreflective or poorly implemented digitisation, and the misuse or inadequate protection of children’s data by some providers. We are also clear that digital technology should be used only minimally, if at all, with children under the age of two.

Wherever you stand in the screen-time debate, there is usually one point of agreement: if screens are used, quality matters. That quality should be determined in terms of its impact on children’s education, verified by strong, reliable scientific evidence.

And that is our mission.

Instead of framing the debate as screen time versus no screens, we focus on what researchers have been advocating for over a decade: the quality of technology and how it supports learning through its interaction with the Cs—content, context, and the individual child.

This does not change with GenAI-enhanced EdTech, by the way. The questions remain the same: what is the evidence on the impact of the content that is offered, in what context, and for whom. Technologies evolve, but their educational impact cannot be assumed and quality is never optional.

In contexts where screens are useful, recommended, or actively desired, we work to ensure that what children encounter on those screens is high quality, evidence-informed, and developmentally appropriate. We are not pro-screen or anti-screen. We are pro-evidence, pro-equity, and pro-quality. And we believe that is where the conversation needs to be.

Having worked with more than 1200 schools over ten years one thing that seriously needs to be looked at is most definitely the quality of screen time in schools. I just wrote a full strategy and governance update for a school because students were on screens up to 5hr a day before they even got home to their personal screens.

And this is why we like working with you at Pickatale! Exactly where the focus should be. Looking forward to discussing further at Bett!